It’s over a year now since I visited the British Library as one of an informal group to look at the Library’s holdings of Vaughan Williams manuscripts; at last I get round to following up the visit with some comments on Vaughan Williams and Blake. Graham Jefcoate had organised this private visit for a few Vaughan Williams enthusiasts, on Wednesday 6th November, 2015, and I was able to tag along. Richard Chesser, Head of Music at the British Library, hosted the meeting and introduced the material: manuscripts from the British Library’s extensive Vaughan Williams collections (both scores and letters). Documents shown to us included, by my request, the manuscripts of Job: a masque for dancing and the Ten Blake Songs. My thanks to Ted Ryan for suggesting I join the group, and to Graham and Richard for organising the afternoon and making some fascinating materials available.

The extensive Vaughan Williams holdings of the British Library include almost all the surviving manuscripts of his compositions (chiefly donated by his widow Ursula) and probably most of his letters, though the extensive correspondence with Edward J. Dent is now in King’s College, Cambridge, and that with Lucy Broadwood is, I believe, in Surrey History Centre (the County archives). One should perhaps note here that the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library at Cecil Sharp House was named in his honour as President of the English Folk Dance and Song Society. The Memorial Library contains, of direct Vaughan Williams interest, only his folksong scrapbooks and his collection of broadsides. I would add that I have found the Memorial Library invaluable for my research into musical settings of Robert Bloomfield.

My personal attitude to Vaughan Williams remains ambiguous. Though greatly admiring of some of his music, above all the Blake settings, I find myself still irritated by the Vaughan Williams cult whereby he’s celebrated for his “Englishness” and promoted by ghastly men like Simon Heffer. Every year it seems there are angry letters to the press claiming the Proms are neglecting “English Music”. This doesn’t mean the writers are calling for more John Dunstable (featured 2016) or Leonel Power (never), or the lost geniuses Thomas Linley (once in 2007) and George Pinto (never). They’re certainly not asking for more of Maude Valérie White (some good Blake settings by her), whose music was last performed at a Prom in 1940, or the spikier music of Elizabeth Lutyens (last performed 1994). Lutyens notoriously dismissed Vaughan Williams, along with the rest of the English pastoral school, as “cow-pat music, with a folky-wolky tune on the cor anglais”. There’s enough truth in that for the criticism to have stuck. Though, just as Vaughan Williams has been lumbered with supposed allegiance to the "cowpat school", so Lutyens herself never escaped her portrayal by Henry Reed as the "twelve-tone composeress" Hilda Tablet. Indeed, when I read anything by Lutyens, the voice I hear has the gruff tones of Mary O'Farrell, who played Dame Hilda.

There’s something about Vaughan Williams that brings out the worst in music critics. Neville Cardus attributes to Vaughan Williams’s music a quality he terms “manliness” (56). Can music or any work of art be gendered in this way? Classical authors specifically assign warlike or manly qualities to the Dorian mode and so on, but this is clearly not what he’s getting at. Neither has he in mind the Baroque “doctrine of the affections”, according to which music can illustrate or imitate various emotional or affective states. Not at all. Vaughan Williams’s music, to Cardus’s way of thinking, is a manly expression of his personal manliness. The earliest reference to “manly music” in this sense that I have found is in 1841, when the critic Henry Chorley announced that “Mendelssohn’s is eminently manly music…” (i, 277). All of it? Famously, Queen Victoria sang her favourite Mendelssohn Lied, “Italien”, with Albert accompanying, to honour the great man’s visit to Windsor. Embarrassed, he had to admit the song was actually by his sister. Songs by Fanny Mendelssohn had been smuggled into her brother Felix’s 12 Gesänge, Opus 8 (1827) and 12 Lieder, Opus 9 (1830).

Byron Adams suggests that Vaughan Williams initiated or at least acquiesced in the insistence of his critics on his music’s manliness, and created for himself a public face that was self-consciously “masculine”. And his later biographers, Percy Young, Hubert Foss, Frank Howes, colluded with the composer to make “British downrightness” the keynote of his public persona, “thereby protecting an ambivalent, intellectual and complex personality from public scrutiny” (33). I also think that for Cardus in particular, reference to Vaughan Williams’s manly music encodes a homophobic gibe at Benjamin Britten. Of course Cardus’s own marriage was a sham, “more amicable than conjugal” (28); Neville and Edith led separate lives in separate cities. When visiting London, Neville stayed at the National Liberal Club, and not in Edith’s flat in Maida Vale. Sad, really.

Arnold Schoenberg supposedly once said that his music was not modern, just badly played. (I have been unable to trace Schoenberg’s alleged remark back to its source. The earliest citation I have so far found is in Melville (xi) but this is clearly not its first appearance; Melville quotes it as though a commonplace that everyone knows and for which there is no need to provide a bibliographical citation. The hunt goes on.) Decades ago I attended a performance of Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Kontakte by Roger Smalley, piano, and Tristan Fry, percussion. Music critics at the time declared the performance impeccable but dismissed the work as “experimental”. I had access to a score of the work and the performance was highly inaccurate with most of the “contacts” missed where piano, percussion and electronics lines should have met. More recently I heard in Edinburgh a performance of the same work given by Pierre-Laurent Aimard and Samuel Favre, with Marco Stroppa, electronics, which was quite simply great music. Stockhausen’s music isn’t experimental, it was just badly played. Benjamin Britten in his diaries constantly criticizes the orchestra at the Royal College as amateurish, and English conductors as incompetent and Adrian Boult, in particular, a “terrible execrable” conductor (56). Meanwhile Vaughan Williams seems to have accepted uncritically whatever performance, however amateur, he was given. And was admiring of Boult. I find that what I want to say of Vaughan Williams is this: his music isn’t English, it’s just badly played.

1928

“Blake’s Cradle Song” (Sweet dreams, form a shade, o’er my lovely infant’s head); for voices in unison with keyboard accompaniment, in E flat.

(Fitch 1287; Kennedy 1996, 117)

In a letter of 23 September 1940 to Ursula Wood, his future wife, Vaughan Williams wrote: “Thank you for the timely present … I know the Blake poems well—but I’ve never felt tempted to set him” (letter 346). There’s some failure of memory here since he wrote a setting of “Blake’s Cradle Song” in 1928. There is apparently no surviving manuscript (at least none I can trace in the extensive British Library holdings) though editorial material may have survived in the Percy Dearmer papers (scattered and not checked).

It was written for and published in

The OXFORD BOOK of | CAROLS | By | PERCY DEARMER | R. VAUGHAN WILLIAMS | MARTIN SHAW | [device] | OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS | LONDON : HUMPHREY MILFORD | 1928Music edition, complete.—xxix, 491 pages of music; 19cm.

<APKD: collection Keri Davies>

Contents: 197 carols of which “Blake’s cradle song” is no 196. There is also an Appendix of “additional folk tunes which are proper to certain carols in Part 1 of this book”.

The Preface (signed P. D.), notes that “… we have arranged the Oxford Book of Carols in a special way. In the First Part we have placed traditional carols which still have their proper tunes … ; in the Second part, traditional carol tunes set to other traditional or old texts; in the Third , the words are not traditional; in the Fourth the tunes are by modern composers; and in the Fifth [carols 186-197] are a few entirely modern carols” (xx-xxi). Most of the carols are arranged for chorus SATB, or for unison voices with keyboard. A few are given in more elaborate versions.

Reprints followed in 1934 and subsequent years. 1964 saw the 25th impression re-engraved and reset. By 1987 it had reached its 34th impression. Oxford University Press also issued in 1928 a Complete words ed.—17cm, a Small words ed. (“Cheap edition”)—11cm (both without music), and a series of selected numbers: Carols from the Oxford Book of Carols, in 78 nos. Then in 1956, OUP issued The Oxford book of carols for schools: a selection arranged for unison singing from The Oxford Book of Carols by Percy Dearmer, R. Vaughan Williams, Martin Shaw.—Piano ed.—London: Oxford University Press, 1956.—56p; 25cm. 50 carols, with music. I have yet to determine if this included “Blake’s cradle song”. There was also a Melody ed.—18cm.

The Oxford Book of Carols is the third collaboration between Dearmer, Vaughan Williams, and Shaw, following The English Hymnal, 1906 and Songs of Praise, 1925. The Blake setting, for solo or unison voices with keyboard accompaniment, is in Part V: Carols by Modern Writers and Composers. The text is over-punctuated, as one might expect at that date, and stanzas 3 and 4 are omitted. Whether this is Dearmer’s or Vaughan Williams’s decision I cannot now determine. Dearmer, on other occasions, showed himself as quite high-handed in editing and cutting texts; while Vaughan Williams incurred the wrath of A. E. Housman for omitting a stanza in his setting of “Is my team ploughing?”.

Vaughan Williams Christmas Carols by Cardiff Festival Choir, conducted by Owain Arwel Hughes with Robert Court, organ.

Maestoso, 1997.—1 CD.

Track 7: Blake’s cradle song

High voices only. Nicely sung with organ accompaniment.

Lullaby: Music for the Quiet Times by The American Boychoir

Albemarle Records, 2002.—1 CD.

“Blake’s cradle song” is track 15.

Unison singing by boys and youths accompanied by flute and strings. Dreadful. Far too slow, turning the lullaby into a sentimental dirge.

Vaughan Williams: Carols, Songs & Hymns by Maddy Prior & The Carnival Band

Park Records, 2011.—1 CD.

Catalogue No: PRKCD 111

<APKD>

Track 2: Blake’s Cradle Song.

Solo voice with a few strings, guitar, clarinet. Perhaps not quite what Dearmer and Vaughan Williams had in mind, but far and away the best performance. The rest of the album is enjoyable too, including “The Divine Image” (track 10, unaccompanied) from the Ten Blake Songs.

Actually, there's a fourth recording—a version by “Sting” (Gordon Sumner). So ghastly I'd suppressed all memory of it.

(“Blake’s cradle song” also received settings by Hugh S. Roberton and Peter Hurford. These too have been recorded and can cause some confusion when searching for the Vaughan Williams.)

It is possible that the inclusion of “Blake’s Cradle Song” in the Oxford Book of Carols was occasioned by the Blake Centenary (100 years after his death in 1827). 1925 had seen the publication of Geoffrey Keynes’s Blake Bibliography, and his edition of the Complete Writings (3 vols.). 1927 saw Keynes’s single volume Blake in the Nonesuch Compendious series as well as the unveiling of a memorial plaque in St Paul’s Cathedral and a stone marking Blake’s grave in Bunhill Fields. The Centenary and Keynes’s intervention certainly supplied the reason for the next Blake-inspired work: Job. A masque for dancing.

Sir Geoffrey Langdon Keynes (1887-1982), surgeon and bibliophile, was born in Cambridge on 25 March 1887. Geoffrey Keynes went to school at Rugby where he was a contemporary of Rupert Brooke, before entering Pembroke College, Cambridge, in 1906, to study natural sciences. He trained at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, and served in the Royal Army Medical Corps during World War I. After the war he became part of the surgical team at Bart’s, where he was appointed assistant surgeon in 1928. He retired from Bart’s in 1952, and received a knighthood in 1955. His literary works include bibliographies (Jane Austen, John Donne, William Hazlitt), biographies (Rupert Brooke, William Harvey), and in particular, studies of William Blake (his 1973 Festschrift lists his over 120 publications on Blake).

1930

“Job. A Masque for Dancing”.

(Fitch 1289; Kennedy 1964, 528-34)

British Library: Music Collections: Add MS 54326

Autograph full score. Ink and pencil on commercially-produced music manuscript paper; ff. ii+204. Original foliation in pen and pencil. 450 x 315mm.

The full score is preceded by the listed instrumentation in ink, apart from “Saxophone” which is added in pencil. Curious.

Copies of the Blake engravings from a printed edition are mounted throughout the manuscript. (My guess, without going back and checking again, is that the illustrations are cut from the edition Reproduced in reduced facsimile from impressions in the | British Museum | LONDON & GLASGOW: | GOWANS & GRAY, Ltd., | 1912. <APKD>)

Contents: Scene 1, Introduction ; Pastoral dance ; Satan’s appeal to God ; Saraband of the Sons of God—Scene 2, Satan’s dance of triumph—Scene 3, Minuet of the sons of Job and their wives—Scene 4, Job’s dream ; Dance of plague, pestilence, famine, and battle—Scene 5, Dance of the Three Messengers—Scene 6, Dance of Job’s Comforters ; Job’s curse ; A vision of Satan—Scene 7, Elihu’s dance of youth and beauty ; Pavane of the Sons of the Morning—Scene 8, Galliard of the Sons of the Morning ; Altar dance and heavenly pavane—Scene 9, Epilogue.

Job is dedicated to Sir Adrian Boult, who regularly included it in his programmes, and by whom it was four times recorded. The manuscript score was (I presume) presented to Boult by Vaughan Williams and in turn presented by Boult to the British Museum Library, 10 February 1968.

The British Library’s Vaughan Williams Manuscripts include other material relating to Job.

Add MS 57286

Second piano part of the two-piano arrangement. [1930] “Corrected copy” (f. i), mostly in copyist hands with a few autograph pages. Pencil annotations. ff. ii+98. 302 x 237mm.

Add MS 50411

Opening page of an arrangement for two pianos. Autograph.

Job as a ballet is not based directly on the Biblical narrative but on William Blake’s series of engravings Illustrations of the Book of Job (1825). Geoffrey Keynes had the original concept of the work, and created the scenario which he sent (translated into French and accompanied by a facsimile of Blake’s engravings) to Serge Diaghilev of the Ballets Russes, but without success. Keynes’s sister-in-law, Gwen Raverat, created the stage design and costumes after Blake. In 1927 Keynes and Mrs Raverat decided to approach Vaughan Williams about music for their ballet (thereby completing a Cambridge triumvirate and also making Job a Darwin family affair, for Mrs Keynes and Mrs Raverat were Darwin cousins of Ralph Vaughan Williams.) Ninette de Valois was brought in to provide the choreography. She was not a Darwin; indeed she wasn’t even a Valois.

The idea took such a hold on the composer that he found himself writing to Mrs Raverat in August 1927, “I am anxiously awaiting your scenario—otherwise the music will push on by itself which may cause trouble later on”. Job was finished early in 1930 and was performed (in its full orchestral version) for the first time by the Queen’s Hall Orchestra at the Thirty-third Norfolk and Norwich Triennial Musical Festival on October 23 that year. It was listed in the programme as “Job: a pageant for dancing”, and was conducted by the composer. The first stage performance (with a reduced orchestration), was given by the Camargo Society, Cambridge Theatre, London, 5 July 1931, conducted by Constant Lambert. Anton Dolin created the part of Satan.

The work was then taken up by the Vic-Wells Ballet who gave their company premiere on 22 September 1931, at The Old Vic Theatre, London, using the version for theatre orchestra made by Constant Lambert. Sets and costume designs were by Gwendolen Raverat. Long excerpts from a performance of Job by the Vic-Wells ballet were televised on 11 November 1936 (Robert Helpmann danced the role of Satan, William Chappell that of Elihu; the performance was probably conducted by Lambert). This was the television debut of the Vic-Wells ballet; the 20 minute programme was broadcast at 15.35 and repeated at 21.35. This all that the Radio Times tells us. I am unclear if there were two live performances or if a filmed performance was broadcast twice.

The work was revived, 20 May 1948, for the Sadler’s Wells Ballet, with sets and costumes now by John Piper. The occasion was a Sadler’s Wells Ballet Gala, at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. The Covent Garden Orchestra had as its guest conductor Adrian Boult. The part of Satan was danced by Robert Helpmann, that of Elihu by Alexis Rassine. Further performances followed throughout the fifties with revivals in 1972 and 1984. I don’t know if Vaughan Williams’s original score or Lambert’s reduction was played for these Covent Garden performances.

The now Royal Ballet production was filmed in 1959. Cinematography was by Edmee Wood and Bryan Ashbridge. The part of Satan was danced by David Blair, that of Elihu by Pirmin Trecu.

An extract from the ballet, “Satan’s solo” was included in Royal Ballet mixed programmes in 2006.

The first version of the music to be published was a piano arrangement:

Job: a masque for dancing, founded on Blake’s “Illustrations to the Book of Job” / by Geoffrey Keynes and Gwendolen Raverat; music by R. Vaughan Williams, pianoforte arrangement by Vally Lasker.—London: Oxford University Press c1931.—Score (41p); 31 cm.The printed edition is surprisingly lavish, with one of Blake’s Job illustrations as frontispiece. Intended for dance rehearsals, it contains more detailed staging directions than are given in the full score.

The piano reduction is an essential component in any ballet production and can itself play a critical role in the balletic creative process. It is a practical, pragmatic realisation of the composer’s vision with which dancers and production team can work. Vaughan Williams, too busy himself, asked Gustav Holst’s amanuensis Vally Lasker to create a piano score (“something simple and practical”) for the rehearsals. It was completed in May 1931 and a copy survives in Oxford University Press’s archive, written in in black ink with stage directions in red, overlaid with numerous pencilled comments and amendments, each reflecting a rehearsal event, a last-minute change, or a refinement to the stage action or choreography. The OUP Blog notes that bars are added where the stage required more music, or deleted when there was too much; re-voicing and corrections to the music are slipped in; stage instructions are changed or elaborated. The creative dialogue between composer, choreographer, and producer is silently re-enacted within this simple, handwritten score. The music of Job thus reached its definitive form through the vehicle of Vally Lasker’s piano reduction.

It was to be another three years before Oxford University Press issued the composer’s full orchestral score, with the rehearsal changes duly incorporated. In 1934 finally appeared

Job: a masque for dancing, founded on Blake’s “Illustrations of the Book of Job” / by Geoffrey Keynes and Gwendolen Raverat; music by R. Vaughan Williams.—London: Oxford University Press, 1934.—Full orchestral score (109p); 35cm.Vaughan Williams’s scenario, or synopsis, printed in the full score differs from Geoffrey Keynes’s. Kennedy reprints both in parallel (529-34).

Job takes from the Stuart masque the courtly dance forms in which it is composed. There are no folk-dances—not even Satan gets a jig. Opinion was divided at the time of the first performances as to how well the work stood up to performance independently of the dance dimension. Now we can see how the careful placing of different elements in the score—the heavenly, the earthly and the infernal, all characterised by a different music style—emphasises the sense of symphonic unity. Job can stand firmly on its own feet as a symphonic suite.

Writers more familiar than I with Vaughan Williams’s other works have commented how material from Job supplies impulses and musical themes for his subsequent symphonies. The violent streak unexpectedly revealed by Vaughan Williams in his Fourth Symphony, on which he started work almost at once after completing Job, can be traced back to the Satanic music of his “masque for dancing”. Then in the music for Job and his family we find elements of the visionary and spiritual world that is later found in the Fifth Symphony. One might also draw comparisons between the ethereal violin solo in The Lark Ascending and the violin solo in “Elihu’s dance of youth and beauty” in Scene VII of Job. A key work then in his oeuvre, it is no accident that the “Pavane of the Sons of the Morning” and the “Galliard of the Sons of the Morning”, together with the calm “Epilogue”, were played at Vaughan Williams’s funeral at Westminster Abbey on 19 September 1958.

The orchestral recordings of Job are listed and reviewed by William Hedley in the RVW Journal. Now the work can also be experienced through the focussed clarity of Vally Lasker’s piano reduction in Iain Burnside’s recent recording for Albion Records.

The sons of the morning: piano music of Ralph Vaughan Williams and Ivor Gurney.

Iain Burnside, piano

Albion Records, 2012.—1 CD.

Catalogue No: ALBCD 015

<APKD>

Track 3: Job: a masque for dancing

Simon Wright comments on the OUP Blog, “The music’s inner voicing, and many points of articulation and phrasing emerge in an entirely new way”.

I must also mention some of the myths surrounding Job. The first myth is that Serge Diaghilev, to whom it was offered, turned it down, considering it “too English”. This hardly makes sense, since Diaghilev had already commissioned Lord Berners’ The Triumph of Neptune to a libretto by Sacheverell Sitwell. The first performance was in December 1926. The sets were based on penny-plain tuppence-coloured toy theatre sheets and you can hardly get more English than that. Keynes (interview reprinted in the RVW Journal), on reflection thought that Diaghilev himself never saw his proposal; Keynes’s letter and accompanying illustrations would have been intercepted and replied to by Diaghilev’s secretary, Boris Kochno, and the refusal came from Kochno. Keynes also noted what he thought were hardly coincidental reminiscences of Blakean gestures and groupings in another Biblical ballet, Le Fils prodigue (libretto by Kochno, choreography by Balanchine, music by Prokofiev, 1929).

Other myths involve Vaughan Williams’s dislike of dancing en pointe, as though this was some disincentive to offering Job to the Ballets Russes. But they didn’t always perform en pointe; there is, for example, no dancing en pointe in L’Apres midi d’un faune (choreography by Vaslav Nijinsky, music by Claude Debussy, first performed by Les Ballets Russes in 1912); the principal dancers wear golden sandals, the coryphées go barefoot. And that’s just what first came to mind. There are no doubt other examples. Then in December 1930 Vaughan Williams wrote to the music critic Edwin Evans, “I want the work called a ‘Masque’ not a ‘Ballet’ which has acquired unfortunate connotations of late years to me” (Letter 188). What on earth is this about? What unmentionable trauma? And as for his comment, in a letter to Gwen Raverat, that he disliked ballet dancers’ “over-developed calf muscles”, this just seems to me an unwarranted gibe at Keynes’s sister-in-law, Lydia Lopokova.

1947

“The Voice out of the Whirlwind”. Motet for mixed chorus (satb) and orchestra or organ.

British Library, Add MS 50467

Full score. Autograph , with the printed vocal score cut up and pasted in. Preceded (ff. 1-2b) by an autograph copy of the words.

Not, strictly speaking, a Blake setting, this is adapted from the “Galliard of the sons of the morning” (Job, Scene VIII) to which Vaughan Williams was able to fit words from the Book of Job (XXXVIII, 1-11, 16-17. XL, 7-10 & 14). It has been suggested that the “fit” of text and music is so uncanny as to prompt the thought that the composer may even have had these very words in mind back in 1930.

The vocal score was published in 1947.

The voice out of the whirlwind : motet for chorus (S.A.T.B.) and organ, the words from the Book of Job, etc.—London: Oxford University Press, 1947.—1 score (18 p.) ; 26 cm.It was written for the Musicians Benevolent Fund’s annual St Cecilia’s Day service and first performed at the church of St Sepulchre, Holborn Viaduct, London, 22 November 1947. The orchestral arrangement was prepared for the Leith Hill Musical Festival four years later. Oxford University Press has the conductor’s score and orchestral parts on hire.

There have been two recordings:

Vaughan Williams: Willow-wood

Roderick Williams, baritone; Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Choir and Orchestra; David Lloyd-Jones, conductor.

Naxos, 2005.—1 CD.

Catalogue No: 8.557798

<APKD>

Recorded February 20-May 8, 2005, Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool.

Track 3 is The Voice out of the Whirlwind: motet for chorus and orchestra (5:15)

The Voice out of the Whirlwind is, I think, better heard here in the orchestral version.

Vaughan Williams: Sacred Choral Music

The Choir of Clare College, Cambridge; James McVinnie and Ashok Gupta, organ; Timothy Brown, conductor.

Naxos, 2010.—1 CD.

Catalogue No: 8.572465

<APKD>

Track 1: The Voice out of the Whirlwind (5:23)

The Voice out of the Whirlwind is given here in its original version for choir and organ (Clare’s organ scholar, Ashok Gupta, provides an exceptionally vivid accompaniment).

1957

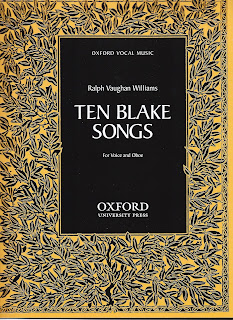

Ten Blake Songs for voice and oboe. Composed Christmastide 1957. Words by William Blake.

(Fitch 1290; Kennedy 1964, 639; Kennedy 1996, 237)

British Library: Music Collections: Add MS 50481 (bound with four other works)

A bound volume of Vaughan Williams Manuscripts. Vol. CXXI (ff. 107).

Contents: Three Shakespeare Songs, for unaccompanied chorus.—Seven songs from “The Pilgrim’s Progress”, for voice and piano.—Along the Field, eight songs for voice and violin. Words by Alfred Edward Housman.—Ten Blake Songs, for voice and oboe.—Three Vocalises, for soprano and clarinet.

The Ten Blake Songs are ff. 69-103. The manuscript was originally “6 Blake Songs”. This scrawled title was then crossed out and “Ten” substituted.

Rough score on commercially-produced music manuscript paper, arranged in the order of the published songs except that nos. 5 and 6 are reversed. Autograph. There are two scores for no. 8, followed (ff. 95-103) by an oboe part in the hand of Gus de Mauny, a copyist regularly used by Vaughan Williams.

The Blake Songs were swiftly published.

Ten Blake songs for voice and oboe / R. Vaughan Williams; [words by] William Blake.—London: Oxford University Press, c1958.—1 score (14p.; 31cm.).—Publ. no. 60810. Later reissue (undated) ISBN: 0193459523 <APKD>For tenor or soprano: 1. t or s.—2. t.—3. t or s.—4. t –oboe silent.—5. t.—6. t or s –oboe silent.—7. t.—8. t or s.—9. t or s –oboe silent.—10. t or s .

In 1957, the Blake Bi-Centenary Committee commissioned Ralph Vaughan Williams to compose Blake settings for its film The Vision of William Blake, which were later published as Ten Blake Songs—for high voice and oboe. Membership of the Bi-Centenary Committee consisted of Professor Anthony Blunt, George Goyder, Sir Geoffrey Keynes, H. M. Margoliouth, Sir Herbert Read, Professor Vivian de Sola Pinto, Kerrison Preston, Rev. F. Heming Vaughan and Miss D. M. Vaughan. I had assumed that Geoffrey Keynes was the prime mover behind the commission as he already been instrumental in commissioning Job. (Keynes has somewhat of a reputation as a bully and could well have forced through the decision to get his wife’s cousin to write the music for the film.) There are however letters from Keynes in which he denies all involvement. Though Vaughan Williams was already an old man, he had considerable experience in writing film scores.

A musical setting is, so to speak, an interpretation of a poem: it is the composer’s understanding of the words, made audible by means of his or her choice of pitch, tessitura, accentuation, and phrasing in the vocal line, and choice of style, mood, and implied action (if any) in the accompaniment. The best Blake settings bring Blake’s words firmly into our own time. The songs chosen for Vaughan Williams to set were: “Infant Joy” (from Songs of Innocence), “A Poison Tree” (from Songs of Experience), “The Piper” (from Innocence, there titled “Introduction”), “London” (from Experience), “The Lamb” (Innocence), “The Shepherd” (Innocence), “Ah! Sun-flower” (Experience), “Cruelty Has a Human Heart” (Experience), “The Divine Image” (Innocence), “Eternity” (from Auguries of Innocence, closing words). The result has an austere beauty removed from Vaughan Williams’s usual line of English pastoral.

Ursula Vaughan Williams provides an unsatisfactory account of the Blake Songs’ commissioning and composition, perpetuating the myth of Vaughan Williams the bluff and downright.

A short job that came Ralph’s way was the writing of some songs for a film. The Blake Centenary had suggested a film of Blake’s pictures, and music was needed for it. The film makers brought screen and machinery and ran the film through and showed Ralph the poems they would like him to set. At first he was not at all enthusiastic. He had always admired Blake as an artist, but he did not care greatly for his poems. However, he said he would see what he could do, stipulating that the songs should not include ‘that horrible little lamb—a poem I hate’.

He had nothing much to do after our carol party, so he considered the poems and decided it would be interesting to set them for tenor and oboe; it was a match to dry tinder, for no sooner had he decided on the means than the tunes came tumbling out. He wrote nine Songs in four days and one morning he said with rage, ‘I was woken up by a tune for that beastly little lamb, and it’s rather a good tune’. So he had to set the poem after all. (386)There’s no sense here that Ursula had any grasp of how Vaughan Williams went about composing; and no sense that she understood how tremendous these songs are. To me they’re his masterpiece at the closing of a long life. Ursula seems quite dismissive of the Blake Songs, whereas I think that they represent Vaughan Williams’s supreme achievement as a songwriter and at the cusp of a late style.

Ursula also sets up what I think is another of those Vaughan Williams myths. On a first examination of the manuscript, “The Lamb”, supposedly inspired in sleep, has just as many scratchings-out and scribbled-over and amended bars as any of the other songs.

The Ten Blake Songs are not his only works for voice and melody instrument. The bound volume of Vaughan Williams Manuscripts Vol. CXXI also contains Along the Field, eight songs for voice and violin (1927) and Three Vocalises for soprano and clarinet (1958). These are sometimes thought to demonstrate the influence of Gustav Holst’s Four Songs, op. 35, for voice and violin (1905), as is perhaps the case with the earlier set (1927) where the violin part is clearly an accompaniment, quite unlike the soloistic oboe part of the Blake settings. Now the elderly composer unexpectedly shows the influence of a much younger man, Benjamin Britten. Vaughan Williams’s word-setting in the Blake Songs is indebted to Purcell (of course) but also to Britten’s post-Purcell example particularly his setting of English poetry in his Serenade (1943). Donald Fitch has noted how “composers have often been seduced by the seeming simplicity of [Blake’s] poems ... into using trite harmonies and an all too tempting triplet rhythm that seems to fit rather too easily the metre of the poems” (xxv). Britten’s setting of Blake’s “The Sick Rose” is a masterly lesson in how to set English words that is responsive to Blake’s metric in a way no other composer had achieved. Additionally, I would suggest that the oboe writing owes something to Britten’s Metamorphoses after Ovid for solo oboe. Of course, one can refer back to Bach’s oboe obbligati to some of the most wonderful vocal writing in the cantatas and that influence surely applies, but I still think that the music of Vaughan Williams’s younger contemporary, pared-down, yet wonderfully expressive, is an important influence in the last years of his life. (One might compare the influence of Boulez’ Le Marteau sans maître on late Stravinsky.)

In the nearly sixty years since his death, Ralph Vaughan Williams has maintained his local reputation as a significant British composer. But, unlike Britten or even Elgar, he has still to catch on abroad. Despite a wide-ranging catalogue of works: choral works, symphonies, concertos, and operas, and work for all levels of music-making, hardly anything has been recorded by non-English artists. The chief exception is the Ten Blake Songs where oboists, such as Bart Schneemann, have initiated recordings. The oboe is so clearly an equal with the voice, not at all in an accompanying role, that it’s not surprising that the Blake Songs (at least some of them) appear on oboe-devoted CDs.

Vaughan Williams: Ten Blake Songs and Linden Lea; and music by Howells, Ridout, Steptoe and Warlock.

Meridian, 1988.—1 CD.

Catalogue No: CDE 84158

<APKD>

James Bowman, countertenor; Downshire Players of London (Paul Goodwin, oboe d’amore).

Tracks 13-22: Ten Blake Songs.

Transposed down a third. The score itself authorises downward transposition, for example if the oboe part is played on clarinet.

Vaughan Williams: Songs of Travel, Ten Blake Songs; Butterworth: A Shropshire Lad.

London, 1991.—1 CD.

Catalogue No: 430 368-2

<APKD>

Robert Tear, tenor; Neil Black, oboe.

Tracks 12-21: Ten Blake Songs.

Originally issued on LP, 1972. I find Tear’s reedy tenor just too much when combined with Black’s rich oboe sound.

Benjamin Britten, Ralph Vaughan Williams, Felix White: 20th century English music for oboe.

Canal Grande, 1993.—1 CD.

Catalogue No: CG 9326

<APKD>

Nienke Oostenrijk, soprano; Pauline Oostenrijk, oboe.

Track 7: Infant Joy.—Track 8: The Piper.—Track 9: The Shepherd.—Track 10: Cruelty has a human heart.—Track 11: The Divine Image.—Track 12: Eternity.

Vaughan Williams: On Wenlock Edge, Ten Blake Songs, Four Hymns, Merciless Beauty, The New Ghost, The Water Mill.

EMI Classics, 1996.—1 CD.

Catalogue No: CDM 5 65589 2

<APKD>

Ian Partridge, tenor; Music Group of London (Janet Craxton, oboe).

Tracks 10-19: Ten Blake Songs.

Originally issued on LP, 1974. Currently my favourite recording.

Vaughan Williams: Along the Field, On Wenlock Edge, Merciless Beauty, Ten Blake Songs, and other songs.

Hyperion, 2000.—1 CD.

Catalogue No: CDA 67168

<APKD>

John Mark Ainsley, tenor; The Nash Ensemble.

Tracks 6-15: Ten Blake Songs.

It takes two—Bart Schneemann—oboe.

Channel Classics, 2002.—1 CD.

Catalogue No: CCS 18598

<APKD>

Johanette Zomer, soprano; Bart Schneemann, oboe.

Track 16: Infant joy.—Track 17: Cruelty has a human heart.—Track 18: The piper.—Track 19: Eternity.

Ralph Vaughan Williams: Oboe Concerto, Ten Blake Songs, Household Music, Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis.

Capriccio, 2010.—1 CD.

Catalogue No: 5035

<APKD>

Andreas Weller, tenor; Lajos Lencsés, oboe.

Tracks 4-13: Ten Blake Songs.

Vaughan Williams: Carols, Songs & Hymns by Maddy Prior & The Carnival Band

Park Records, 2011.—1 CD.

Catalogue No: PRKCD 111

<APKD>

Maddy Prior, voice.

Track 10: The Divine Image.

Ralph Vaughan Williams: Ten Blake Songs & On Wenlock Edge; Jonathan Dove: The End; Peter Warlock: The Curlew.

Harmonia Mundi, 2013.—1 CD.

Catalogue No: HMU 807566

Mark Padmore, tenor; Britten Sinfonia (Nicholas Daniel, oboe).

Tracks 13-22: Ten Blake Songs.

Britten: Serenade for tenor, horn and strings, Simple symphony; Vaughan Williams: Ten Blake songs.

Santa Fe Pro Musica, 2014.—1 CD.

<on order 01/12/2016>

John Elwes, tenor; Thomas O'Connor, oboe.

Tracks 13-22: Ten Blake songs.

1958

The Vision of William Blake.

Colour film. 16mm. Duration: 27 minutes.

Narrated by Robert Speaight and with poems read by Bernard Miles. Oboist: Janet Craxton. Singer: Wilfred Brown. Edited by Dennis Lanning. Written and directed by Guy Brenton.

Production: Morse Films, British Film Institute Experimental Film Fund, Arts Council of Great Britain, British Council, The Blake Film Trust.

The film soundtrack incorporates extracts from Job, and eight of the Ten Blake Songs. Nos 2, “A Poison Tree”, and 3, “The Piper”, were excluded. The film was first shown publicly, 10 October 1958.

There’s a lot more to write about Vaughan Williams and Blake, particularly his role in creating Blake the hymnodist in his arrangements for The English Hymnal and elsewhere. But that must be left for another time.

Sources and Further Reading

Byron Adams, “‘No armpits, please, we’re British’: Whitman and English music, 1884-1936”

in Lawrence Kramer, ed.—Walt Whitman and modern music.—New York: Garland, 2000.

Benjamin Britten.—Journeying boy: the diaries of the young Benjamin Britten 1928-1938.—London: Faber, 2010.

<APKD>

Neville Cardus.—‘My Dear Michael ...’: cricketing & other extracts from Neville Cardus’s letters to Michael Kennedy, 1959-74; edited by Bob Hilton.—Manchester: Lancashire CCC Library, 2007.

<APKD>

Henry F. Chorley.—Music and manners in France and Germany.—3 vols.—London: Longman, 1841.

Donald Fitch.—Blake set to music: a bibliography of musical settings of the poems and prose of William Blake.—Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

<APKD>

Job, and The rake’s progress / by Joan Lawson, James Laver, Geoffrey Keynes, Frank Howes.—London Bodley Head 1949.—Sadler’s Wells ballet books no 2.

<APKD>

Contents: Ninette de Valois as choreographer / by Joan Lawson—Imaginary landscape with figures / by James Laver—Job / by Geoffrey Keynes—The music of Job / by Frank Howes—Appendix.

Journal of the RVW Society, no 19 (October 2000).

Accessible from http://rvwsociety.com/.

Issue includes “Focus on Job”: Deborah Heckert, “‘A typically English institution’: a context for Vaughan Williams’s Masques”.—“Job: the stage directions scene by scene”.—William Hedley, “Job: a masque for dancing: an introduction and CD review”.—Michael Kennedy, “Vaughan William’s [sic] Job”.—Sir Geoffrey Keynes, “The origins of Job”.—Frank W. D. Ries, “Sir Geoffrey Keynes and the ballet Job”.

Michael Kennedy.—A catalogue of the works of Ralph Vaughan Williams.—2nd ed.—Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Michael Kennedy.—The works of Ralph Vaughan Williams.—London: Oxford University Press 1964.

2nd ed.—1980.

Sir Geoffrey Langdon Keynes: Personal Papers and Correspondence (c. 1906 – 1982)

Cambridge University Library, Department of Manuscripts and University Archives: MS Add 8633.

34 boxes received from the library of Sir Geoffrey L. Keynes, 1982.

Of particular interest would be Box 30: Ballet papers: file on Camargo Society; envelopes containing ballet programmes, and Marlowe Society programmes; file on the Job ballet; volume of cuttings on the Job ballet, 1948. When I explored the Keynes papers in 1990 or thereabouts my focus was on the Blake facsimilist William Muir. I don’t think I ever got as far as Box 30.

The John Rylands University Library, Manchester, holds the Michael Kennedy Papers, with Kennedy’s correspondence with Geoffrey Keynes relating to the first danced performance of Job (5 July 1931), and the film, The Vision of William Blake (1958), with which Keynes claims no involvement.

Stephen W. Melville.—Philosophy beside itself: on deconstruction and modernism.—Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1986.—Theory and history of literature; 27

OUP Blog.

http://blog.oup.com

With a photograph of a page from the manuscript of Vally Lasker's Job piano reduction.

Radio times.—National ed.—Vol. 53, issue 680 (9 October 1936).

Accessed via http://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk/ .

Schedules from 11 October 1936 to 17 October 1936.

Henry Reed.—Hilda Tablet and others: four pieces for radio.—London: British Broadcasting Corporation 1971.

Contents: “A very great man indeed”.—“The private life of Hilda Tablet”.—“A hedge, backwards”.—“The primal scene, as it were”.

<APKD>

Ralph Vaughan Williams.—Letters of Ralph Vaughan Williams, 1895-1958; edited by Hugh Cobbe.—New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

An annotated edition of 757 letters (selected from a database collection of more than 3,000) written by and to Vaughan Williams.

Ursula Vaughan Williams.—R. V. W.: a biography of Ralph Vaughan Williams.—London; New York: Oxford University Press, 1964.

No comments:

Post a Comment