Just over a month ago, on 1st December 2021, MacDougall Arts, of St. James's Square, held one of their regular sales of Russian works of art. Included in the auction was a portrait of Catherine II, Empress of all the Russias, otherwise Catherine the Great, by Dmitry Levitsky (1735-1822), together with a letter from Catherine to Count Piotr Aleksandrovich Rumiantsev outlining her inoculation strategy against smallpox. (The two items together sold for £951,000, if that’s of any interest.) This sale was the impetus or trigger for a talk I gave to the Blake Society AGM (19 January 2022). The title I gave it : “Inoculation should be common Everywhere”, derives from this letter by Catherine the Great.

Catherine is depicted half-length, wearing the tiniest crown with a laurel wreath and the ribbons of the most important Russian decorations—the Orders of Saint Andrew the First-Called, Saint Vladimir 1st class and Saint George 1st class. Levitsky created some twenty images of the Empress, although there is no evidence to suggest that Catherine ever posed personally for him. In keeping with a practice that was widespread at the time, the painter used earlier portraits by the Austrian Johann Baptist Lampi the Elder as templates when working on his compositions. What looks like a good naturalistic portrait in Western European style has been developed within the traditions of icon painting.

Remarkably, Levitsky has managed to represent a real person and not merely copy the template offered to him. The Empress as portrayed by Levitsky looks more youthful than in Lampi’s canvases; the modelling of the face has been slightly altered and its oval shape softened, the figurative treatment made less formal, and the monarch’s lips have taken on a restrained half-smile.

But of greater significance on this occasion is Catherine’s letter on inoculation against smallpox. The letter was signed by her on 20 April 1787 and contains an instruction to Count Rumiantsev in Kiev, as governor-general and vice-regent of Malorossiya (“Little Russia”, a name for Ukraine used in official documents of tsarist Russia) to treat smallpox inoculation in the province as one of the main “duties” of his position, so that “such inoculation should be common everywhere”.

Smallpox was one of the most feared illnesses of the eighteenth century, when epidemics ravaged Europe in the 18th century and often claimed the lives of entire villages. It is said that in one year in the second half of the eighteenth century, two million people died of smallpox in Russia. Smallpox began with a high fever and severe vomiting, followed by a skin rash. The victim would next develop sores, which eventually scabbed over and fell off, scarring the skin. About three out of 10 of those infected died, and the survivors were typically badly scarred for life, sometimes even blinded, or permanently disabled. Scars from earlier encounters with the disease covered the bodies and faces of people in all social classes. Indeed, Catherine’s future husband, Grand Duke Piotr Fedorovich, later Tsar Peter III, fell victim to smallpox just before their wedding, and was left permanently disfigured by the pockmarks.

The 1787 letter predates Edward Jenner’s medical breakthrough of vaccination by cowpox by nearly 10 years. Before Jenner, European physicians followed Turkish practice in relying upon variolation (variola is Latin for smallpox), a deliberate infection with a mild form of the disease. While those who received the treatment did go on to develop common smallpox symptoms like fever and rash, the death toll following variolation was significantly lower. Typically, mortality after inoculation by the “variolation” method was 2%, some 20 times less than from natural infection. But the risk remained, and there were many opponents of variolation.

The Empress herself and the heir to the throne, Grand Duke Paul, had been inoculated against smallpox some twenty years before she wrote this letter, but the task of inoculating the population of the Empire remained incomplete and was still meeting with resistance on the ground.

Ever since my childhood, I was aware of the horror of smallpox, and at a more mature age it took a great deal of effort to alleviate that horror ... Last spring, when the disease was rampant here, I used to run from house to house ... not wanting to endanger my son or myself. I was so struck by the vileness of such a situation that I considered it a weakness not to avoid it. I was advised to inoculate my son against smallpox. I used to reply that it would be shameful not to start with myself, and how could I introduce smallpox innoculation without setting a personal example? I began to study the subject ... Should I remain in real danger, together with thousands of people, throughout my life, or should I prefer a lesser danger, a very brief one, and so save many people? I thought that by choosing the latter, I was selecting the best course ....

In October 1768, Catherine started the preparatory diet and medicinal treatment. Dimsdale harvested the contents of a smallpox pustule from the young son of a sergeant-major and used it to inoculate the Empress.

Horace Walpole gives an account in a long gossipy letter, 2 December 1768, to his friend Horace Mann in Florence:We have a new Russian Embassador, who is to be Magnificence itself. He is wonderfully civil and copious of words. He treated me t'other night with a pompous relation of his Sovereign Lady's [that is, Catherine’s] heroism—I never doubted her courage. She sent for Dr Dimsdale; would have no trial made on any person of her own age and corpulence: went into the Country with her usual company; swore Dimsdale to secrecy, and you may swear he kept his oath to such a Lioness. She was inoculated, dined, supped, and walked out in public, and never disappeared but one day; had a few [pustules] on her face and many on her body, which last I suppose she swore Orloff [her lover, Count Grigor Grigor’evich Orlov] likewise not to tell. She has now inoculated her Son—I wonder she did not, out of magnanimity, try the experiment on him first.

The Empress was inoculated secretly in the night between Sunday and Monday, 12-13 October. Everything turned out well and, after a week of mild discomfort, the Empress’s recovery was triumphantly announced on 29 October. Her son was inoculated soon after. The Synod and the Senate sent greetings to Catherine, and 21 November 1768 was declared a day of celebration in Russia to honour Her Imperial Majesty’s “magnanimous, unparalleled and illustrious deed”.

An allegorical ballet, Prejudice Defeated, was staged at the court theatre, while, for the common people, a start was made on producing pictures in popular prints that promoted inoculation. Unfortunately, the fashionability of being inoculated against smallpox amongst the nobility did not trickle down to the Russian population at large, particularly in the outer regions of the empire. The Empress’s letter of 1787 shows again that the problem of smallpox inoculation in the outlying parts of the Empire was still acute and called for administrative intervention and supervision.

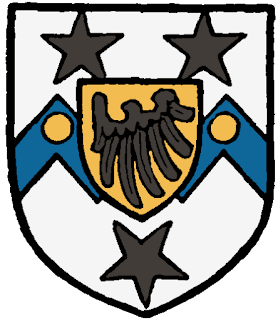

Dimsdale was rewarded with the rank of Baron of the Empire, Counsellor of State, and Physician to the Empress, besides a reward of £10,000, a pension of £500 per annum, and £2,000 expenses. He had also permission to add to his arms a wing of the Russian eagle in a gold shield. His son, Nathaniel, shared his honours; he too received a Barony, and was also presented by the Grand Duke Paul, “as a testimony of his regard”, with a gold snuffbox.

Starting with me and my son, who is also recovering, there is no noble house in which there are not several inoculated persons, and many regret that they had smallpox naturally and so cannot be fashionable. Count Orlov, Count Razumovsky and countless others have passed through Mr Dimsdale’s hands—and even renowned beauties... Here is what example means.

On his return to England Dimsdale was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society and, sometime after this, Dr or Baron Dimsdale, as he was now called, opened a banking house in Cornhill, in partnership with his sons and other relatives. Although he himself retired from the firm in 1776, the business was continued by his descendants. The success of the Dimsdale bank rested on its appeal to a clientele which was largely upper-middle-class, nonconformist, and often related by blood or marriage to the partners.

In 1780 he was elected member of parliament for the borough of Hertford, after which he declined all medical practice except for the relief of the poor. He went once more, however, to Russia in 1781, when he inoculated Catherine’s grandchildren, the Princes Alexander and Constantine. He was re-elected to parliament in 1784, but did not stand in 1790, and was succeeded by his son Nathaniel. Dimsdale died at Hertford on 30th December 1800, aged eighty-nine. He came from a long line of Quaker medical men (his grandfather Robert Dimsdale, surgeon, had accompanied William Penn on a visit to America in 1684) and was interred in the Quaker burial ground at Bishops Stortford. Dimsdale had lived to see the publication in 1798 of Edward Jenner’s work on vaccination, which eventually triumphed and put an end to the earlier practice of variolation.

Nathaniel himself died in 1811 with no male heir and his Russian title lapsed. The Barony awarded to his father, however, descended via his eldest son John (1747–1820) to succeeding generations. The current Baron Dimsdale is Edward, the 10th baron.

In 1767 Dimsdale had published an important treatise on variolation: The Present Method of Inoculating for the Small-Pox, a work which became very popular and in the course of three years ran through at least seven large editions, and was translated into Russian in 1770. Dimsdale’s later treatises on inoculation included Thoughts on General and Partial Inoculation (1776), Observations on the Plan of a Dispensary and General Inoculation (1780) and Tracts on Inoculation (1768 and 1781).

One might note here that Dimsdale’s notable clients included Omai (c.1753-c.1780), the first Tahitian to visit England. Omai arrived in Britain on 14th July 1774 and was taken by Joseph Banks to see the king on the 21st (there were newspaper accounts the next day). Shortly afterwards (possibly at King George's urging) he was taken by Banks to Baron Dimsdale in Hertfordshire to be inoculated against smallpox. It's not certain whether it was the King or Banks who suggested Omai be taken to Dimsdale, but, as George definitely paid for the treatment, it was most likely he. Banks (then still plain Mr Banks, he didn't become Sir Joseph until 1781) took Omai to Hertford on 4th August and stayed with him until Omai was well enough to return to London on an uncertain date between 14th and 17th August 1774. (Dimsdale stressed the need for rest before as well as after inoculation.) Smallpox had killed Omai's compatriot Ahutoru, the first Tahitian to visit Europe, who had been taken to France in 1769 by Bougainville and died of the disease on his voyage home.

Dimsdale’s work on smallpox inoculation was not original but built on the achievements of an Essex family named Sutton, who despite the absence of any formal medical qualifications had achieved outstanding success with their techniques. These consisted of a 2-3-week preparatory diet and drug preparation followed by puncture of the skin with a lancet dipped, to use their own description, “in the smallest possible quantity of the unripe crude or watery matter from the pustules” from a patient suffering from the disease. The incision, one in each arm, was minute: it was not to exceed one eighth of an inch in length nor one sixteenth of an inch in depth. The Suttons operated an Inoculation House at Ingatestone in Essex. They inoculated about 17,000 persons, with only five or six fatalities. Without acknowledging the Suttons by name, Dimsdale established the “Suttonian” method as the standard mode of inoculation for smallpox.

So what has all this to do with William Blake?

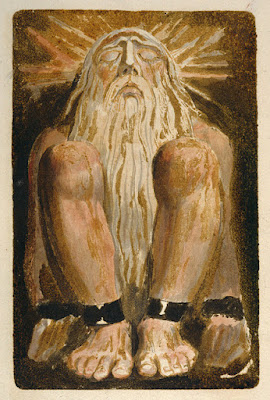

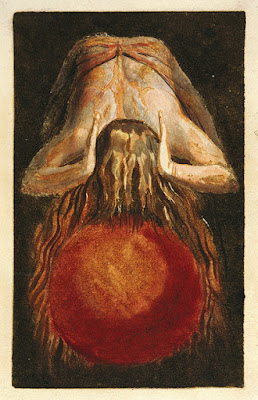

In February 1956, Sotheby’s sold at auction Blake’s First Book of Urizen. Identified as copy A, it was formerly in the possession of Major T.E. Dimsdale, the eighth Baron. It was acquired by Paul Mellon; and given by Mellon to the Yale Center for British Art in 1992.

This copy, originally printed in 1794, remains one of the most striking—as well as most complete—versions. The Sotheby’s catalogue cites a family tradition that the first Baron Dimsdale had acquired the book directly from Blake.

It had previously been issued in colour facsimile with an accompanying note by Dorothy Plowman.

Previously, in 1952, Sotheby’s had sold a fragmentary copy (Copy R) of Blake’s Songs of Innocence. Again, the family tradition, reported in the catalogue, cites the original purchaser as the first Baron Dimsdale. This copy of Innocence shows some signs of fire damage. It was acquired by Geoffrey Keynes and bequeathed by him to the Fitzwilliam Museum in 1985. The museum notes that “This copy was printed and coloured c. 1794”, though Joseph Viscomi suggests a later date of production. To my mind, the light watercolour washes agree with a 1794 date; copies from 10 years later are much more richly coloured. Another fragmentary copy of Innocence (Copy Y, again with fire damage) was acquired by a German collector and is on loan to the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne. It is now clear that these two fragmented copies once formed a single copy. Copy R/Y was presumably broken up while in the Dimsdale family collection, perhaps at the time it was rescued from a bonfire. It may also be the earliest example of a Blake illuminated book decorated with gold leaf.

… The Complaint and the Consolation, or Night Thoughts, [with] 43 pictorial borders designed and engraved by William Blake and coloured by hand, … red straight-grained morocco gilt, uncut, folio, R. Noble for R. Edwards, 1797.Inscribed on the verso of the title page in pencil in the upper left-hand corner is “Baron Dimsdale”. It was sold to the dealers Sims, Reed & Fogg, for £13,750. The dealers then sold it to an anonymous collector for £20,000. It is now listed as Copy X of the coloured Night Thoughts. Bentley suggests that Blake was given copies of the Night Thoughts to colour as part payment for his work. The coloured engravings, of a luminous beauty like that of the original watercolours, would have been sold directly to Blake’s patrons.

There’s thus a Dimsdale provenance for the Book of Urizen (copy A), Songs of Innocence (copy R/Y), and the hand-coloured copy of Young’s Night Thoughts (copy X). This, surely, is a significant Blake collection, almost certainly bought directly from the poet-painter and thus strong evidence of at least acquaintanceship and probable friendship between Blake and the first Baron Dimsdale. (Of course, Thomas and Nathaniel Dimsdale were both the first Baron, of separate creations; but that doesn’t really alter the picture of a strong link between Blake and the Dimsdales.)

It’s puzzling that so little has been written on the Blake-Dimsdale connection. I suppose that Blake’s friendship with a fashionable society physician, banker, and member of Parliament doesn’t fit the standard picture that puts Blake firmly within the circle of Joseph Johnson (what Richard Cobb dismissed as a mere bunch of “misfits, cranks, dreamers, and dissenting radicals”). One imagines the Communist Party Historians Group (E.P. Thompson, A.L. Morton, and the rest) sitting around talking about the Johnson circle: “Ooh, they’re just like us”. As indeed they were.

Dimsdale was a Quaker, and the Friends’ London Meeting for Sufferings had first petitioned parliament against the slave trade in 1783. He was one of the initially small group of MPs who supported the Society for the Purpose of Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade from its inception in 1787. And also as a member of parliament, the Quaker Dimsdale consistently voted against the Pitt government’s war plans. Unlike the Johnson circle which just talked about it, Dimsdale was actively trying to do something.

So were William and Catherine Blake inoculated? I think they must have been. Dr Dimsdale as friend and patron would surely have encouraged it. I am tempted to suggest that maybe approaching Dr Dimsdale for inoculation was the occasion of their meeting and the start of their friendship. Extraordinary as it seems, there’s a real possibility that an obscure physician in Hertfordshire had inoculated both Catherine Blake and the Empress Catherine of Russia.

Sources and Further Reading

Philip H. Clendenning.—“Dr. Thomas Dimsdale and Smallpox Inoculation in Russia”.—Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Vol. 28,No. 2 (April 1973) 109-12.

John Griffiths.—“Doctor Thomas Dimsdale, and Smallpox in Russia: The Variolation of the Empress Catherine the Great”.—Bristol Medico-Chirurgical Journal (January 1984).

E.H. McCormick.—Omai, Pacific envoy.—Auckland University Press, 1977.

MacDougall Arts.—Important Russian Art: auction sale.—1 December 2021.https://macdougallauction.com/en/catalogue/43

Karen Mulhallen.—“The Crying of Lot 318; or, Young’s Night Thoughts Colored Once More”.—Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 19, Issue 2 (Fall 1985) 71-72.

Lucy Ward.—The Empress and the English Doctor : how Catherine the Great defied a deadly virus.—London : Oneworld, 2022.—333 pages : illustrations (black and white), facsimile, portraits ; 24 cm.Published in April 2022, long after I had completed this post. Will fill in much of the detail that I omitted or simplified.

Other names that I could have mentioned

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762), who introduced variolation (smallpox inoculation) into England; Onesimus (fl. 1706-1721), African-born slave, who introduced smallpox inoculation into North America; Cotton Mather (1663-1728), Puritan minister, who took the credit.

No comments:

Post a Comment